As a foreign policy expert focusing on East Asia, Ryan Hass’s foreign service career spanned 15 years, during which he was stationed in U.S. posts in Seoul, Taiwan, and Beijing. He also served as Director for China, Taiwan, and Mongolia on the National Security Council under President Obama. Hass has published multiple research papers on U.S.-China relations and is a frequent guest on interviews and podcasts with the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Foreign Affairs.

In this interview, Hass elaborates on his policy recommendations from a paper he published on June 4 - Why Should America Negotiate with China? He discusses differences in policies and negotiating styles across the Obama, Biden, and Trump administrations, and shared his thoughts on key determinants in sustainability in U.S.-China interactions on Taiwan and trade. He credits Obama and Biden for building a largely constructive relationships with China, while describing the Trump administration’s China negotiations as unconventional and conflict prone. Hass also strongly objected to American or Chinese isolationism and calls on a future generation to resolve the Taiwan conflict in a creative way.

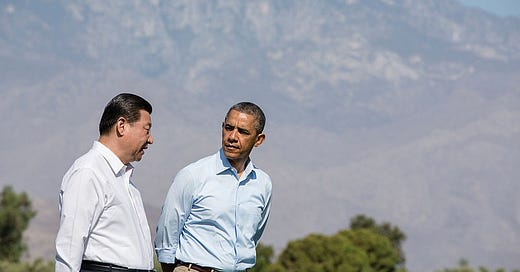

Edison Chen (EC): Mr. Hass, you served as the China Director on President Obama's National Security Council. What role did China play on President Obama's agenda? What were some major China decisions the National Security Council made while you were there?

Ryan Hass (RH): The Obama administration’s foreign policy feels like a distant memory. So much has changed from then until now. Broadly speaking, President Obama wanted to preserve American global leadership and use it to steer the international system in ways that supported advanced U.S. interests and values. Issues like democracy, free markets, respect for individual liberties were fundamental to the Obama administration’s approach to the world. President Obama believed that, for America to lead, it must tackle the most urgent and most important global challenges. He also believed that America’s capacity to tackle global challenges would be enhanced if the United States and China were capable of coordinating efforts in a common direction. Much of the discussion during that period between the United States and China was around whether and how to address challenges like climate change, the spread of Ebola, keeping Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons capabilities, and promoting global financial stability.

Of course, there were also areas of friction, such as cyber issues, the South China Sea, human rights, and issues in Taiwan. However, the broader point is that President Obama viewed China within the global context: what the United States was working to accomplish and how its relationship with China related to those goals. President Obama’s approach opened him up to criticism for not being tough enough and pushing back against Chinese advances. When President Trump ran in 2016, he made a very strong argument that China’s industrial growth had hollowed out America and caused the losses of many American blue-collar jobs. Many Americans felt like they were losing hope because of China’s success. I think if we’re going to be fair in our review of history, we would have to acknowledge that the Obama administration’s policy towards China did harden considerably in his final years. President Trump certainly added his flourishes and his personality to this hardening of approach, but the shift was underway under President Obama.

EC: You said that President Obama became harder on China towards the end of his administration. In January, you were quoted in an op-ed calling the Biden administration timid in dealing with China. Comparing President Biden to Obama, or to President Trump's first term, why did you call his administration timid? What role did the first Trump administration’s China policies play in Biden’s agenda-setting?

RH: In fairness, the Biden administration did many things right on China. They made considerable progress in strengthening America’s alliances. The United States’ economy was strong at the time President Biden left office, and we had considerable success during the Biden administration in attracting top talent from around the world to live, study, and work in the United States. However, I have a critique of the Biden administration’s approach to China, and it largely falls in two categories.

The first category is that the Biden team approached China as a political issue rather than a strategic challenge. Politics drove policy rather than the other way around, and this affected the way that the Biden administration spoke about and addressed issues with China.

The second critique I would offer is that the Biden administration was either unable or unwilling to articulate any sense of direction to its strategy on China. They never explained to the American people what the United States is trying to achieve on China. Reiterating and being a steward of strategic competition is not an approach that engenders enthusiasm or gives any sort of sense of direction. The lack of a narrative arc creates a narrative vacuum, and that vacuum naturally gets filled by discourse around the risks that China poses to the United States. This leads to pressure towards securitization of America’s approach to China. Now I think there’s much more focus on the risks than on the future opportunities for the U.S.-China relationship.

EC: How would you evaluate the China negotiations that happened during the terms of both President Obama and President Biden? How is Trump different in those negotiations? What are the pros and cons of a Trump negotiation compared to predecessors?

RH: My view is that the Obama and Biden administration pursued what I think would be referred to as a traditional or professional approach to U.S.-China negotiations. It would begin among experts and then work its way up progressively to the two leaders. President Trump has a very different negotiating style. He values being unpredictable: he starts with a broad declaration of threat. It will escalate if China retaliates and will deescalate if China comes to the negotiating table. He constantly improvises and adjusts until he believes progress is made, which would allow him to declare a victory. Whereas Biden and Obama really relied upon experts and professionals to advance negotiations, President Trump prefers to work from the top down to provide his personal input in the negotiating process to secure better deals. It’s too soon to tell which approach will yield better results, but if we look at the first term of the Trump administration, there’s not a lot to show for it. He negotiated a phase one trade deal, which he touted as the breakthrough deal, and it vastly underperformed. We’ll see it if this approach does better in his second term.

EC: Following up on that, could you talk about an example in which a president used their very distinctive negotiation to reach agreements with China?

RH: This is hard to quantify because we’re talking about problems that were avoided, which is oftentimes the mark of very successful diplomacy. One example was there was a significant concern from 2015 to early 2016 that China’s island-building campaign in the South China Sea would extend to Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea, which is a feature that was contested by China and the Philippines. The Philippines is a treaty ally of the United States. In the end, through a very detailed negotiations that moved up to and included the two presidents, there was an understanding reached that averted a confrontation that would implicate America’s alliance commitments. I think that that was an outcome of a varied, intensive, detailed, and professional process. That’s an example of a problem or crisis averted. I think an example of opportunity seized was how the United States and China worked together during the global financial crisis to put a floor underneath the global economy to synchronize their respective economic efforts so that they have maximal impact to help move the global economy out of the sharp descent.

EC: Let’s talk about your current role as the director of the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution. You recently published a paper titled Why Should America negotiate with China? What are the main points you make in your paper and why talk about negotiation now?

RH: Thank you for noticing the paper. The research began after President Trump entered office, and it was driven by an awareness that there was a hardening groupthink within the Trump administration that negotiations with China are futile or worthless. This is not a view that I believe President Trump shares, so the purpose of the paper was to offer a rationale to why the United States should negotiate with China and how it could most effectively do so. The starting point for the argument is that the United States is simply incapable of sealing itself off from China. What happens in China affects the United States for good or for ill, not because the United States and China like each other, but because leaders in both countries have a responsibility to navigate this relationship and negotiate with each other.

Part of the work of the paper was to try to draw lessons from past administrations that could be applied to help the current administration be more effective at negotiating with China than its predecessors. As I dug into the research, I tried to offer a distillation of the purpose of negotiation with China. What I came up with was that there are four purposes. The first is to clarify top priorities and concerns that the United States and China have to shrink space for miscalculation. The second is to mitigate the risk of conflict. The third is to capitalize on opportunities for coordination where there are shared challenges and aligned interests. The fourth is to resolve areas of dispute that are ripe for solutions. It would be irresponsible for leaders to not undertake those efforts in my judgment.

EC: Many U.S.-China scholars have written that the two countries are on the verge of a Cold War. However, you pointed out in your research that the United States and China have agreed to cooperation on issues such as narcotics controls. What are some areas in which the Trump administration could work with China? Is there reason to believe the Chinese government can trust the Trump administration?

RH: Many people in the Trump administration feel as though the United States and China stand too far apart from each other to negotiate mutually beneficial outcomes, that the United States must harden themselves for competition with China, and that previous efforts to negotiate with China have bestowed dignity and respect upon the Chinese leadership without providing benefits to the United States. Many in the administration believe that their effort could be spent more productively negotiating with other countries in order to strengthen America’s position for dealing with China as an adversary. I don't share that view. I wrote the paper to try to push back against that view.

With these two countries negotiating, there are a few facts that I think that we must hold in mind. The first is that both the United States and China are great powers, but neither country is capable of dictating terms to the other. Both countries are peers, and if there is going to be any coordination between the two countries, it will need to be mutually beneficial for it to be saleable, and I do believe that there are areas where that is possible. I will just put two on the table. The first is on law enforcement issues. America has been pretty outspoken about its concern about the flow of fentanyl precursors entering the United States. Many of those precursors originate in China before they travel to Mexico and eventually into the United States. It’s a very significant factor in how many Americans think about China. Similarly, China has law enforcement challenges of its own, including fraud and online scams that target Chinese citizens. America has pretty good capacity in addressing those issues, so it is space for both countries to work to help each other out. The second issue that I would point to is on risk mitigation. There is no constituency in the United States that wants a war with China, and I do not believe there is any constituency in China that would like to see a war with the United States.

But there are risks of conflict between our countries, and it would be in the interest of both leaders to find ways to limit or mitigate those risks. There are things they can do so that would serve both sides’ interests without providing any security concession to each other. For example, working to prevent out-of-control scenarios for large AI models would be in both countries’ national interests. Building rules around the use of cyber in areas that are out of bounds for cyber-attacks such as hospitals would be mutually beneficial. Limiting the creation of orbital debris in space, given that the United States and China are two of the largest space fairing nations in the world, would serve both countries’ national interest and would not be a favor to either side. Thus, there are areas where it is possible and mutually beneficial for both sides to coordinate together.

For your second question, I’m a bit reluctant to speak for the Chinese government on what their views are. My best analysis is that the pessimism about the usefulness of negotiations is not something that is unique to the United States. I think that there is a high degree of pessimism in Beijing too about whether there is space for progress. I think that there’s a broad view that in Beijing that China just needs to harden itself because America will be implacably hostile so long as China is rising.

EC: One other major area of conflict, especially in recent years, is the issue of Taiwan and the strategic overlaps of the two major powers there. You mentioned China’s military modernization and the leaps it has made. What have been some of the Chinese military’s major advances in your time of observing U.S.-China relations? What implications do these advancements have on the fate of Taiwan?

RH: China has launched the most ambitious peacetime military buildup of any major power since World War II. China has vastly expanded its naval capacity, its missile capacity, and is embarking on a very ambitious nuclear military modernization. As a result of these efforts, the United States no longer has localized military supremacy over China in Asia and around the Taiwan Strait. There’s much more parity between American and Chinese forces than with other competitors for many decades. As a result, there’s a growing concern in Washington about whether capabilities equal intentions. In other words, whether China’s military buildup is for the purposes of preparing to launch a military attack against Taiwan. I think that the intensity of this concern has grown as China’s military capabilities advanced.

EC: President Biden publicly committed to protecting the Taiwanese government from a potential Chinese military invasion. However, President Trump has not explicitly supported the same position. Are we facing a scenario where neither China nor the U.S. establishment are willing to make concessions on Taiwan, but President Trump may be willing to finally make such compromises?

RH: I don’t see evidence at the moment that President Trump is preparing to make compromises on Taiwan. I think it’s worth recalling that the Trump administration during its first term strengthened rather than weakened America’s relationship with Taiwan, but your question is right that President Trump has been unwilling to match former President Biden’s statement of blanket support for coming to Taiwan’s defense. In this respect, President Trump is returning America’s policy posture towards dual deterrence, trying to deter Taiwan from taking steps that could drag the United States into a conflict that it did not choose, but also trying to deter China from taking aggressive steps towards seizing Taiwan by force. In this respect, President Trump in his own way, is preserving an equilibrium on the Taiwan issue.

EC: During President Obama’s term, China did have some high-level exchanges with officials from Taiwan. Xin Jinping met Lian Zhan and Ma Yingjiu, former Kuomintang presidents. Could you describe President Obama’s Taiwan strategy?

RH: President Obama was very comfortable with communications across the Taiwan Strait. He understood that America’s overriding interest and objective was to preserve peace and stability, and to create conditions that would allow leaders on both sides of the Strait to resolve their differences. He just was firm that the way that they resolve the differences should be nonviolent. Thus, that was a traditional American posture. President Trump is more unconventional as a leader. President Biden was willing to make statements of unlimited support for Taiwan’s defense in ways that no previous president has felt comfortable doing. It largely reflected a view by President Biden that allies and security partners are assets that are good for the United States and that America should be instinctively supportive and protective of its allies and partners.

EC: Do you think that the leaders in Taiwan play an important role in U.S.-China relations? Do you think the Democratic Progressive Party factored into current tensions?

RH: China’s position has been that it is prepared to engage with any other leaders that accept and endorse the 1992 consensus, but the 1992 consensus really doesn’t have a lot of purchase in Taiwan today, and if that remains the precondition for China to engage directly with Taiwan’s elected leaders, we could face a long-time absence of direct communication across the Taiwan Strait. That doesn’t serve anyone’s interest. I think communication enables clarity and clarity shrinks space for miscommunication. My hope is that leaders on both sides of the Taiwan Strait will find creative ways to communicate with each other and to clarify the intentions and expectations of both sides.

EC: Your paper described U.S.-China relations as competitive and interdependent. In that regard, what impacts did the U.S. tariffs have on large U.S. companies and small businesses? We understand that China has been trying to achieve self-sufficiency. Is the United States underestimating China's importance in its economy?

RH: I do believe that the United States is underestimating China’s economic strength and resilience. Many in Washington, D.C. tend to focus on the problems that exist in China’s economy. These problems, like youth unemployment, demographic challenge, debt, and flattening productivity, are real. At the same time, China’s economy also has considerable strengths in the electric vehicle industry, in advanced manufacturing, in clean energy technology, and in batteries and drones. Any attempt by the United States to try to isolate and cut China off from the global economy will not have success. The Trump administration needs to understand that China has economics, but it also has politics. And politics will drive decision-making around how China approaches the trade war much more than the economic activities, and the politics in China tend to push China’s leaders to stand firm in defending China’s national dignity and economic interests, and not being seen as capitulating to President Trump or American pressure.

EC: You suggested that, based on America and China's domestic interest, they both have incentives to strike deals with each other. Could you explain what is stopping them from completing such deals?

RH: Actually, in Geneva, both sides agreed to a truce by withdrawing control over certain choke points. However, I’m a bit concerned that neither side appears to have written anything down on paper. In the absence of a detailed understanding, I worry that we will find ourselves back having to adjudicate the same questions over and over again. To use political science jargon, the trade relationship is more positive-and-negative sum than it is zero sum in that there will not be a clear winner or a loser. Both sides will either be mutually helped or mutually hurt depending upon how they approach the trade relationship. Both countries have dominance in certain choke points in critical supply chains. In China’s case, it is rare earths. For the United States, the choke points are jet engine parts and equipment for the production of high end semiconductor chips. Both sides are capable of weaponizing these choke points. I think rules are needed on weaponization of critical supplies that the other country depends upon. This is not going to happen overnight. I think it will require patient, intensive, detailed, fair-minded, and constructive negotiations. Neither side has yet invested personnel or prioritized such a process for finding rules around weaponization of critical supplies, but I hope this becomes an area of focus going forward.

EC: In the conclusion of your report, you warned of a lose-lose scenario for China and the United States. What is your reasoning behind that conclusion? If both the United States and China lose, does anyone else on earth stand to be a benefactor from that?

RH: It’s a great question to end on. My argument is that both the United States and China are major powers, and neither side can impose its will on the other. These are two proud countries led by strong leaders. Even though it’s probably a low likelihood that the two countries will find a path forward in the near term, the United States and China are going to have to figure out how to live together because we are both trapped on the same earth and neither country can escape from it. I’m also mindful that these efforts may need to await a new generation of leaders who have a vision for the future and see value in pursuing a race to the top where each country competes to best marshal resources and organize coalitions to tackle global challenges.

I do not believe it is impossible in the future because I do not believe that anything about the U.S.-China relationship is predestined or predetermined. The relationship is a relationship that rarely travels along a straight line for very long. It constantly surprises, and in the current moment, the discourses in Washington and Beijing about the relationship are focused on risks. However, there will be a new generation of leaders who will be interested in imagining the future and building a vision for the future. I hope that when that new generation of leaders emerges, we as a community will have equipped them with a framework and a set of recommendations to support their efforts.

Edison Chen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies Public Policy at Duke University.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.

Peace is always on the back foot. To promote peaceful cooperation between the United States and China, all content from the Monitor is provided here for free. If you would like to contribute to our work, please feel free to make a donation to The Carter Center. Please indicate your donation is for China Focus.

That’s all from Atlanta. Y’all be good.